On the horse kills a snake. The miracle of george about the serpent

Read in 4 minutes

The inhabitants of the big city of Gebala, on the Palestinian side, turned their backs on God and worship idols, venerating them according to traditions and according to the royal command. God repays the inhabitants of Gebal by faith and their deeds: a huge Serpent appears in a nearby lake, which comes out of the water and devours people. The entire population of the city turns to the king to advise him on how to avoid adversity. The king, however, tells them that he spoke with the gods and they told him the following: each inhabitant of Gebal should daily give his son or daughter to be eaten by the Snake, until the turn of the king comes, which also must give his only daughter. Everyone agrees with this decision, and everyone, starting with the king’s close associates and ending with the poorest and simplest people, daily, crying and moaning, take their children to the shore of the lake, leaving them to eat a terrible monster. Finally, no one in the city had more children left, and again everyone turned to the king, so that he would fulfill his promise.

The king tells them that he will give his daughter to be eaten by the Serpent, and then he will wait for the gods to open him. The tsar’s daughter is tied up in scarlet, taken to the shore of the lake and left there alone. But George, the holy martyr, a sufferer for the faith of Christ, who lived after death, by God's permission, longs to save the inhabitants of Geval from adversity and, in the form of a simple warrior, is at this hour on the lake. When he sees the virgin, he asks her what she does by the lake alone. She begs the young man to leave these places as soon as possible, and after much persuasion he admits to him that the king, her father, not wanting to leave this prosperous city, agreed with the command of the gods: to give the Snake all the children for eat until he comes turn.

But the great martyr George urges the virgin to not be afraid of anything and offers a prayer to God, asking Him to show His mercy on him, an unworthy slave, and to overthrow the fierce beast, so that all, seeing this, believe that there is only one God, and there are no other gods, except Him. A voice from heaven answers George that his request has been heard. Virgo hears the terrible whistle of the approaching Serpent and again begs the young man to run away and leave her alone, so that he would not die with her. But St. George, upon seeing the terrible Serpent, draws the sign of Christ on earth, and in the name of Jesus Christ demands that the cruel beast submit. By the power of God and the prayers of the sufferer for the faith of St. George, the serpent’s knees are broken, and George and the virgin bind him, taking the reins from the horse and the belt from the virgin’s dress. She leads a terrible beast into the city, and the Serpent drags helplessly and dutifully after her.

All this time, the king and the queen mourn their only daughter. When they see how she leads the bound Serpent, and St. George comes in front, the tsar and the queen are frightened and run away. But George urges all the inhabitants of Gebal not to be afraid, but to believe in our Lord Jesus Christ, in which alone is salvation. Upon learning that the name of the beautiful young man is George, everyone, as one, raises his voice, exclaiming: "By you we believe in one God, the Almighty and in the only begotten Son of our Lord Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Life-giving Spirit." George cuts off the head of the terrible Serpent with his sword, and the king and all the inhabitants of Geval give praise to God. The king orders to build a church in the name of the great martyr and sufferer for the faith of George and from now on to remember him in the month of April.

St. George, seeing that they all believed in our Lord Jesus Christ, promises to show them a new miracle. When the construction of the church is completed, he sends the masters his shield to hang from the holy altar. And since then, the shield has been hanging in the air without any support. Everyone who faithfully comes to this church, through the prayers of St. George, is healed of sorrows and illnesses and rejoices when they see the miraculous deeds of the saint.

Retold

The last quarter-end of the XIV century. Rostov lands

48.7 × 33.6 × 2.2 cm. The tree (linden), the board is whole, there are no dowels, a shallow ark, no breeding ground, gesso, tempera.

No origin established. Was in the collection of S. N. Vorobyov (Moscow), who bought the icon in Moscow in 2002. Acquired for the museum in 2008. Inv. No. ChM-438.

Disclosed in 2002 by S.N. Vorobiev. Re-restored in 2008 by M. M. Bushuev (GRM).

Insertion of a new tinted gesso in the upper and lower corners and on the left margin. Significant late mastics with recordings were left on the right leg of the horse and its croup with a partial approach to the background, a small insert on the neck of the horse. Slight crumbling over the entire surface. The paint layer is worn, especially in the shadow parts of the face, on the blue robes of George, at the borders of the background with the halo. Throughout the middle ground and in the fields there are numerous traces of nails that strengthened the salary. Author's cinnabar inscriptions, double lay on the husk and spear of good preservation.

The composition of the icon is based on one of the episodes of the Byzantine legend, which was part of the cycle of miracles of St. George and has been known since the 9th century. in the monuments of writing as "The Miracle of St. George the Great Martyr about the Serpent." Her iconography follows a brief scene of the scene (which corresponds only to the climax of this text), which has become widespread in the art of the XIV – XV centuries. In this case, however, the most laconic and very rare iconographic option was chosen, devoid of any narrative details: there is no blessing right hand of God; the saint is represented without a shield, a permanent attribute of a warrior; there is not even a hint of the character and place of action - not only ordinary slides, but even manure, sometimes used for the shortest possible runs. George riding on a black horse strikes with a spear a serpent, wriggling right on the light background of the icon, and indeed having the appearance of a serpent, and not a dragon (as it is depicted on most of the icons of this plot) - without wings and clawed legs. Similar images are rare: such a serpent is shown, for example, in the icon of the Rostov circle from the collection of M. V. Rozanova (British Museum, London), which occurs with Pinega, or in the work of the first half of the 16th century. (?) from the collection of I.S. Ostroukhov (Tretyakov Gallery). However, the closest analogy is the icon of the turn of the XIV – XV centuries. of Rostov origin from the collection of K.V. Voronin, which is already the next stage in the development of the plot composition. But even in it such a feature is repeated as the intended pattern of snake scales. The contrast between the large horse, which was hardly inscribed in the middle field, not flying, but galloping heavily, and emphasized by a small, fragile snake that does not look like an evil dragon at all, also painted in sky blue, deprives the icon of the accent usual for such scenes ideas of serpent farming: opposing faith and good to evil, paganism. The monument seems to revive the ancient Byzantine tradition of depicting George the Horseman or the equestrian warrior-triumph and resembles rare examples of the scene where the serpent is not present at all, although the pose of a saint is kept, waving a spear and delivering a blow, as on a Novgorod monument of the late 14th century from the churchyard of Luboni (GRM). Meanwhile, the calmly lowered tail of the horse is more consistent with the amble than with the swift running of the animal.

Other features of the composition - a galloping horse, a high-handed hand of a horseman thrusting a spear into the open mouth of a dragon, and also widely fluttering behind his back, like a red cloak filled with energy of movement - are typical for icons of the XIV-XV centuries. Despite the laconicism of iconography, a horse harness is depicted in great detail and reliably: a high saddle and two blankets (as was supposed to be the solemn exit of the rider), harness, reshma, cinnabar belts and ribbons, elegantly pulling the croup, and especially the red cords tied to the legs, cutting at running. The ceremonial appearance of the horse corresponded to the significance of the victorious rider - it is obvious that the composition was based on an ancient, apparently Byzantine, model.

The laconic, deprived of any narrative context image likened the image of George, the warrior and the snake-ginger, to the heraldic symbolic sign, which was reinforced by another iconographic sign of the image - the black suit of the horse - bringing it together with a small group of works, mainly of central Russian origin, distinguished by this rare feature: with an icon of the middle of the XIV century. from the collection of A. V. Morozov (Tretyakov Gallery), the previously mentioned Pinezhsky image from the collection of M. V. Rozanova, an icon of the 15th century. (?) from the collection of R. Lakshin (Switzerland), two icons of the last third of the 15th century. from private collections and several monuments of the XVI century. The image from the collection of the Museum of Russian Icon among them is one of the earliest.

There is no convincing explanation for replacing the traditional white color of the horse in this scene. The antithesis "white - black", meaning "life - death", "paradise - hell", "light - darkness", in the Christian sense, was by no means reduced to the opposition of good and evil. It permeates the biblical narrative, liturgical poetry and coloristic symbolism of the pictorial structure of the icon. The death of Christ, which became the key to a new life, predetermined the attitude to the “end” and “darkness” as to the “beginning” and resurrection, therefore the semantics of black in icon painting were ambiguous. Along with white, red and red, the black horse is mentioned in biblical texts, especially in the Apocalypse. According to the interpretation of Andrei of Caesarea, the rider on a black horse, who appeared at the time of the removal of the Third Seal (Rev. 6, 5-6), means "crying for those who fell away from faith in Christ because of the severity of torment." George, having won the crown of the victor with his triumph over incredible torment, “having made death straightened by death”, with the help of his horse could symbolically cancel the punishment of the apocalyptic image, just as Christ who stepped on the head of the serpent with His Sacrifice and Light abolished the black darkness of hell and death.

The iconographic features of the icon, which bring it most closely to the Central Russian or Rostov circle, are consistent with its artistic style, which also gravitates to the art of Rostov lands. Archaic methods of processing the front side - a slightly outlined ark, an auripigment-filled background with double cinnabar frames and a two-tone red-brown husk, bright, coarse inscriptions - go back to the picturesque tradition of the north-eastern lands of the middle - second half of the 14th century.

It is also indicated by technical features: the absence of a pavolok, a personal letter without a sankiric base using an auripigment, placed on layers of a transparent light pad with long thin whitening lights, as well as a moving and active final drawing, giving the outline a soft three-dimensional shape. With minimal resources, the master achieves the effect of high relief, almost sculptural appearance, the very type of which is elongated, with a convex forehead and a hairdo pulled back, giving the image a mournfully majestic expression, also belongs to the art of the last decades of the XIV century

This time corresponds most of all to the contrast between rounded monumental shapes and piercingly sharp, fragile details, folds (the pulled-out edges of George's dress or the cone-shaped end of the cloak), as well as between slightly hypertrophied details: George's exorbitantly extended and extended arm and his small leg, which stretches the stirrup . With the Rostov painting tradition, the monument confidently brings together not only the nature of the composition, which has a rich density and activity, when all its components are stretched due to movement along the diagonal (the spear is George’s hand - his exorbitantly elongated fragile body is the leg, the movement of which merges with the horse’s gait), but also, especially, a transparent and delicate coloring, combining the condensed colors of brown and red with light ocher, auripigment and melting blue paint.

Publ.: Museum of Russian Icon. Eastern Christian art from its origins to the present day. Meeting directory. Tom. I: Monuments of Antique, Early Christian, Byzantine, and Old Russian Art of the 3rd – 17th Centuries / Ed. I.A. Shalina. M., 2010. Cat. No. 2. P. 50–53 (text by I.A. Shalina).

Απολυτίκιον Ήχος δ" Ως τών αιχμαλώτων ελευθερωτής, καί τών πτωχών υπερασπιστής, ασθενούντων ιατρός, βασιλέων υπέρμαχος, Τροπαιοφόρε Μεγαλομάρτυς Γεώργιε, πρέσβευε Χριστώ τώ Θεώ, σωθήναι τάς ψυχάς ημών.

April 23 / May 6 - memory of St. vmch George the Victorious († 303) : http://expertmus.livejournal.com/30966.html

The miracle of George about the serpent.

1400-1450.

77, 4 x 57 x 2, 8.

The British Museum. 1986,0603.1.

Provenance. The first owner of the icon was Maria Vasilyevna Rozanova, who found it in 1959 in the parish church of the Ilyinsky Pogost on the Pinega River, where the icon was adapted as a window sash. It was originally cleared in 1960 by Adolf Ovchinnikov in the workshops of Grabar. After clearing it became clear that it was updated several times. Under the layer of the 18th century, a layer of the 17th century was opened, and then a layer of the 14th century. The icon was recognized as an unconditional masterpiece of ancient Russian icon painting.

The son of Maria Rozanova and Andrei Sinyavsky, born in 1964, received a name in honor of the icon “The Miracle of George about the Serpent” they discovered on Pinega. After leaving for emigration in 1973, Maria Rozanova sold the icon favorably at the Axia Art Islamique et Byzantin (dealer / auction house; Liechtensteiner) auction, from where it was purchased at the British Museum in 1986.

An unusual feature of this icon - the black color of the horse - is found on several Novgorod icons of the XIV-XVI centuries, such as “Miracle of St. George »mid-XIV century from the collection of A.V. Morozova (State Tretyakov Gallery), “George the Snakebucker” from the village of Stanily, Lviv State Museum of Ukrainian Art, “Saint George, Nikita and Deesis” of the 16th century in the Russian Museum, as well as on a number of northern Russian icons, for example, “The Miracle of Saint George and the Life” from They are stable in the first half of the 16th century.

It turned out that in the sixties, when the fashion of Russian antiquity spread among the Moscow intelligentsia, the writer Andrei Sinyavsky and his wife Maria Rozanova began to travel to the North for icons, and in one of these trips to Pinega they purchased the “Miracle of George about the Serpent”, brought they decided to show him to Moscow. The icon made a strong impression on art critics. Yamshchikov writes that “the thing was absolutely amazing”, “a masterpiece from masterpieces”.

Former director of the Russian Museum, an amazing connoisseur of ancient Russian painting Nikolai Petrovich Sychev stood in silence for several minutes before the icon, and then said: “This is a masterpiece of world significance. He has a place in the best museums in the world. ”

Blog of the research team of the Andrei Rublev Museum.

Experts cite the church community as an example - the community of the Museum of Ancient Russian Culture and Art named after Andrei Rublev.

The Life of St. George describes many miracles performed by the great martyr. In the earlier version of the life, St. George appears only as a great martyr, and only later versions are supplemented by a description of miracles, and at first there were three episodes characterizing the saint as a miracle worker, then six more were added to them, including the famous “The Miracle of George about the Serpent” .

The first miracle, which can be arbitrarily called the “Miracle with the widow’s column”, or “The widow’s mite”, tells how in Syria, where there were no large stones for the pillars that were supposed to support the building, these stones were bought in distant lands and brought by the sea. So did one widow who bought a good pillar and begged the mayor to take him on a ship in order to take him to the temple of St. George the Great Martyr. He did not heed the prayers of the poor woman and sailed away, and she fell to the ground and, sobbing bitterly, called in the prayers of St. George. In tears, she fell asleep and saw in a dream George appeared on a horse, asking what she was so mourning about. The widow told the saint about her grief. "Where do you want to put the pillar?" asked the saint. “On the right side of the church,” the woman replied. Then the saint wrote on the pillar with his finger, where this gift of the widow should be placed at her request. Together with the woman, they raised a pole, which suddenly became light, and lowered it into the sea. Waking up, the widow did not find the pillar in the same place, and when she returned home, it turned out that her pillar with the inscription made by the saint’s hand was already lying on the shore. The mayor repented of his sin, and the pillar of the widow was placed in the place where it was ordered.

The second miracle - “with a pierced image”, tells about the power of the miraculous icon of the saint. In the same Syrian city of Ramel, already conquered by the Saracens, several Saracens entered the church of St. George during the service, and one of them, taking a bow, fired an arrow at the icon of the great martyr.

But the arrow flew up and, falling from there, plunged the arrow into the hand itself. The hand was swollen, very sick, and the Saracen, tormented by terrible suffering, confessed to all his maidservants, among whom were several Christians. They advised the owner to call the priest, and he explained to the barbarian who was holy George and why he received the grace from God to work miracles. On the advice of the priest, the Saracen ordered to bring the icon of the great martyr George to his house, put it over his bed, prayed in front of her and greased his hand with oil from the lamp. Saracen was healed, believed in God, secretly baptized, and then began in the city square to preach loudly the teachings of Christ as the true God. The convert Saracen accepted the crown of martyrdom, for he was immediately cut into pieces by his former co-religionists.

The third miracle - "about the captured Paflagon youth" tells of the deliverance of a young man captured by the Hagar in the church of the Great Martyr George during the celebration of the saint's memory. He spent a year in captivity with the prince of Hagar, and twelve months later, exactly on the day when the young man was captured by the Gentiles, the prisoner was miraculously returned to his parents through the prayers of his poor mother. He had just served the Hagarian prince at the table and appeared before the startled parents right with a vessel for wine in his hands. Talking about what happened, the young man said: "I poured wine to serve the prince, and suddenly he was raised by a bright horseman who put me on his horse. I held a vessel in one hand, and held on to his belt with the other, and now found himself here ... "

Two more miracles of St. George tell of a similar miraculous return from captivity. However, the most popular of all miracles, firmly entrenched in the iconography of the great martyr, is the “Miracle of George about the Serpent,” where the saint saves the whole city and the royal daughter from a terrible monster.

In the homeland of St. George, near the city of Beirut, where many idolaters lived, there was a large lake near the Lebanese mountains. And in this lake a huge snake settled. Coming out of his refuge, he devoured people, and no one could cope with him, because the very air around him, infected by his breathing, became deadly.

Then the ruler of the country decided every day to give the snake to the children of one of the inhabitants, and when his turn comes, he will give the monster his only daughter.

So by lot the people of that country sent the snake of their children until the turn of the royal daughter came. Dressed in her best clothes and mourned by her parents, she turned out to be a girl on the lake, sobbing bitterly and waiting for her death hour.

Suddenly a beautiful young man appeared before her on a white horse with a spear in his hands - George the Victorious himself. Seeing a crying girl, he turned to her to find out why she was standing on the shore of the lake and what kind of grief she had. But the girl begged the beautiful young man to leave this terrible place as soon as possible, otherwise he would die with her. St. George insisted and finally heard a bitter story about the terrible monster and the king’s word. The girl again begged George to leave, for it was impossible to escape from the monster, and then a serpent appeared from the lake. Having rallied himself with the sign of the Cross, with the words "In the Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit," George rushed to the monster and hit him with a spear, striking it in the throat. The spear pressed the serpent to the ground, the horse trampled it underfoot, and then St. George ordered the girl to tie a serpent with her belt and lead him, as an obedient dog, into the city.

The people shied in horror from the monster, but George said: "Do not be afraid and believe in our Lord Jesus Christ." And when George killed the serpent in the middle of the city, thousands of people believed in Christ and received holy baptism, and there were twenty-five thousand, not counting women and children.

Later, a church was built on that spot in the name of the Most Holy Theotokos and St. George the Victorious, which protects the Christian Church from destructors and from sin, as it preserved the king’s beautiful daughter from the snake-eater.

On May 6, the Church celebrates the memory of one of the most revered Christian saints - the great martyr George the Victorious. His name is associated with many different, sometimes not very consistent legends. Historical motives, church tradition and folk tales are reflected in the iconography of the saint.

St. George. XIV century. Byzantine Museum, Athens

Martyr warrior

The cult of St. George originated in Palestine, in Lydda (Diospolis), where his tomb was venerated from ancient times, and then spread throughout the Christian ecumenical church. Already in the 5th century, a church was built in Rome in the name of St. George, where part of his relics, as well as his spear and gonfalon, were kept. Around the same time, the life of the saint began to take shape. Little historical information about St. George has been preserved, but already in the Vienna manuscript of the IV-V centuries we find a story about his martyrdom. Papyrus fragments of the Acts of George of the VI century are also preserved.

At first, George appears as a confessor of Christianity, defending his faith in front of the emperor Diocletian (in folk tales - before the unfaithful king Dadian), but over time, the image of George as the protector of the weak and oppressed is formed, which is expressed most of all in the plot of the fight against the serpent and the liberation of the young girl. Interestingly, in ancient legends, St. George defeats the serpent not by arms, but by means of prayer, after which he preaches to the people, and according to him people are baptized.

According to legend, St. George lived in the III century in Cappadocia (according to other versions - in Palestine). He was the son of wealthy and noble parents who professed Christianity; his father died as a martyr for Christ when George was still a child. After the death of his mother, at the age of 20, he enters the military service. Gifted with intelligence, courage, physical strength and beauty, George achieved a high position, became a military commander close to the emperor Diocletian. But when the persecution of Christians began, George appeared before the emperor, declared himself a Christian and denounced Diocletian. He was arrested, severely tortured, and beheaded in 303 (304).

St. George defeating the dragon. Paolo Ucello. XV century. London National Gallery.

St. George defeating the dragon. Paolo Ucello. XV century. London National Gallery.

The miracle of the icon "Our Lady of the Sign" (Battle of Novgorod with Suzdal). The middle of the XV century, the State Tretyakov Gallery

The miracle of the icon "Our Lady of the Sign" (Battle of Novgorod with Suzdal). The middle of the XV century, the State Tretyakov Gallery

St. George with the saved youth. Greek icon of the 16th century. GIM

St. George with the saved youth. Greek icon of the 16th century. GIM

Patron of the nobility

The church honors St. George as a great martyr. All over the world we find his images on icons and paintings, in temple paintings and book miniatures, on crosses and panagias, in heraldry and sculpture.

The earliest images of St. George have been preserved in Egypt: this is a fresco on the pillar of the Northern Church in Bauite, as well as the encaustic icon “Our Lady on the Throne with archangels and sv. Theodore and George ”from the monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai. Both images date back to the 6th century. On the fresco, St. George is depicted as a warrior, in all military vestments, with his sword held high, on the icon - in a white tunic, with a cross in his hand.

The main iconography of St. George was formed in Byzantium, where he was very revered. Byzantine emperors, often sourced from the military nobility, considered St. George their patron saint. His images were on coins and seals of the Komnin and Paleolog dynasty.

In Byzantine art, the image of George the warrior - in armor, with a shield, sword and spear - was combined with the symbols of martyrdom - a cross and a red cloak. From the earliest images, his appearance acquires recognizable and stable features: he is a beardless young man with a pretty face and a cap of curly hair. George is often portrayed along with other martyr soldiers - Dimitriy of Solunsky, Theodore Tyrone, Theodore Stratilat, etc.

Not later than the end of the XII century, the iconographic plod of George appeared on the throne, but this is a rather rare type. Also rare is the image of George in prayer, when the saint is depicted in a three-quarter U-turn before Christ, with hands raised in prayer. Already in the post-Byzantine period, an image appears, called Kefaloforos, when the saint is depicted with a truncated head in his hand. Such a haul was popular in Crete in the 16th-17th centuries.

The miracle of George about the serpent. Novgorod, XV century. Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

The miracle of George about the serpent. Novgorod, XV century. Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

St. George. 12th century icon from the monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai

St. George. 12th century icon from the monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai

St. George. XI century. Novgorod the Great. Now it is in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

St. George. XI century. Novgorod the Great. Now it is in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

Serpentine

But the most beloved in the whole Christian world was the image of George on a horse, striking a snake ("The Miracle of George about the Serpent"). Some of the earliest images of this type were preserved on the walls of cave temples in Cappadocia, in the Goreme Valley (late IX - early X century). St. George the Ophiuchus becomes especially popular in the 14th century, when the veneration of holy warriors takes on the meaning of spiritual resistance to the Ottoman Turks, who crowded Christians in the Balkans. During this period, an image also appears with a lad rescued from captivity, who is depicted sitting in the saddle, behind George ("The Miracle of George with the lad").

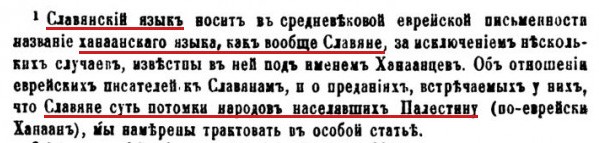

The plot of “The Miracle of George about the Serpent” exists in many versions. For example, in the Greek versions of the legend this miracle is described as the only lifetime, and in the Slavic tradition it is considered posthumous.

The legend says that not far from the place where St. George was born, near Beirut (in a number of texts the city of Lasia or Gebal is called, in the land of Palestine), there lived a serpent that devoured people. And the inhabitants of that locality, out of fear of the monster, decided to regularly give them a young man or a girl by lot by lot. Once a lot fell on the daughter of the ruler. She was taken to the shore of the lake and tied. In horror, she began to wait for the appearance of the snake. When a terrible beast came out of the lake and began to approach it, suddenly George appeared on a white horse, struck the snake with a spear and saved the girl. He not only stopped the destruction of people within Beirut, but also converted to Christ the inhabitants of that country who were pagans.

The “Miracle of the Serpent” is well known in all Christian countries, but especially where the folk tradition was strong: in Asia Minor, Southern Italy, Georgia and Ancient Russia. Saint George was surrounded with special veneration in Georgia, where he was considered the heavenly patron of the country, the very name of which comes from the estate of George. Images of the saint, scenes of his life and miracles are in almost every Georgian church. The translation of the life of St. George into Georgian was made in the 9th century, and already in the 11th century a developed iconographic cycle of the life of the saint appeared in Georgian art. Perhaps it was due to the fact that Saint Nina, enlightener of Georgia, came from Cappadocia and, according to legend, Nina and George were related. One of the earliest images of St. George is considered the relief of the end of the VI century on a small stele from Brdadzori (Kartli, Eastern Georgia). On the western frieze of the Martville Temple (VII century), the image of a horseman on a horse, striking a human figure, which researchers also consider the image of St. George, has been preserved. But this is doubtful, because such an iconographic exodus corresponds to St. Demetrius of Solunsky, and not to George.

The miracle of George about the serpent with worldly hallmarks. Novgorod icon of the XIV century. The Russian Museum.

The miracle of George about the serpent with worldly hallmarks. Novgorod icon of the XIV century. The Russian Museum.

The miracle of George about the serpent. 12th century fresco from St. George's Cathedral in Staraya Ladoga.

The miracle of George about the serpent. 12th century fresco from St. George's Cathedral in Staraya Ladoga.

Beloved Saint of Russian Princes

In ancient Russia, the great martyr George was also one of the most revered saints. He was considered the patron saint of princes and warriors. Many Russian princes bore his name. So, the son of Vladimir the Baptist of Rus, the Kiev prince Yaroslav the Wise in baptism was called George. He set up a temple in Kiev in honor of his heavenly patron. This temple was consecrated by Metropolitan Hilarion on November 26, 1051, and the day of the autumn celebration of St. George was named St. George's Day. In the Kiev Hagia Sophia Cathedral, built by Yaroslav the Wise, the northern chapel was consecrated in honor of St. George, and the earliest of the life cycles of the great martyr (40s of the XI century) was preserved in it. In imitation of the Byzantine emperors, Yaroslav ordered to depict George on silverware and seals. One of the surviving seals shows a half-figure of a warrior and a Greek inscription: "Lord, help your servant George, archon."

In early Russian icons, the image of George emphasized his powerful physique, physical beauty and firmness in faith. This is the image on the bilateral icon of the 11th century from the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. This is a saint, ready to stand for faith until death. He is depicted waist-deep, in armor, with a spear in his right hand and a sword in his left, a red martyr's cloak is thrown over his shoulders.

The icon of St. George (now in the Tretyakov Gallery) also dates back to pre-Mongol time. It comes from Novgorod, from the St. George Cathedral of the St. George Monastery, founded in 1119 by the great-grandson of Yaroslav the Wise, Mstislav Vladimirovich, also named in baptism George. The icon is large (230 x 142 cm), on it the saint is represented in height, with a spear in his right hand and a sword in his left, with a round shield behind his left shoulder. The head of George is decorated with a precious crown.

Yuri Dolgoruky, the head of the dynasty of Vladimir-Suzdal princes and the founder of Moscow, also considered his heavenly patron the great martyr George. In 1152, he laid the stone St. George Church in Vladimir. The image of George adorned the princely seal of Yuri Dolgoruky.

A relief image of George on a horse is found on the facade of the Cathedral of St. Demetrius in Vladimir (90s of the XII century). Under the prince of Vladimir Georgy Vsevolodovich, St. George's Cathedral was built in Yuryev-Polsky (1230-1234).

St. George, XIII century. Museum of History and Ethnography of Svaneti, Mestia Village, Samegrelo and Zemo Svaneti Territories, Georgia

St. George, XIII century. Museum of History and Ethnography of Svaneti, Mestia Village, Samegrelo and Zemo Svaneti Territories, Georgia

St. George, XIII century. Byzantine Museum, Athens.

St. George, XIII century. Byzantine Museum, Athens.

The miracle of George about the serpent. XVI century, Pskov school. Pskov State United Historical, Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve.

The miracle of George about the serpent. XVI century, Pskov school. Pskov State United Historical, Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve.

The miracle of George about the serpent. XVI century. Tretyakov Gallery

The miracle of George about the serpent. XVI century. Tretyakov Gallery

Egoriy the Brave

The fresco of St. George Cathedral in Staraya Ladoga (circa 1164) also belongs to the pre-Mongol period, on which George is represented on horseback. But the rider does not hit the serpent, as is usually the case, he only tramples on him, while the princess leads the serpent on her belt, as if on a leash. Such an unusual interpretation refers us to the Russian spiritual verse about Yegorii the Brave, in which the liberated princess helps St. George to tame the serpent by tying his neck with her silk belt. In this case, we see that the serpent - as a symbol of evil - is not defeated, but tamed, evil is eradicated by transformation, and not by killing the creature. It is no coincidence that folk legends attributed to Yegor the Brave "the assertion of the Orthodox faith in Russia and the eradication of Basurmans in Russia."

In the pre-Mongol period, characterized by high princely culture, images of St. George as a martyr warrior, patron of princes and warriors predominate. During the time of the Tatar yoke, the Christian faith penetrates deeper into the popular milieu, and the image of St. George the Serpent, which expresses the people's aspirations for the help of heavenly intercessors, begins to prevail.

George enjoyed special love in Novgorod and was even considered one of the patrons of the city. In the annals there is a story about how George helped the Novgorodians to free themselves from the miracle besieging the city. In the famous Novgorod icon “The Miracle of the Icon of the Sign”, St. George, along with other holy warriors, leads the cavalry, driving the shelves of Suzdal from the city walls.

One of the earliest and most vivid examples is the Novgorod icon of the 1st half of the 14th century. It combines historical and folklore layers of life: "The Miracle of George about the Serpent" is placed in the middle and is surrounded by 14 hagiographic hallmarks. George is represented here as a national hero: both a Christian martyr and a heavenly deliverer. His figure is fragile and elegant, with all his youthful appearance he resembles an angel. The horse and rider easily soar without touching the ground. Here, as in the Ladoga fresco, the princess leads a serpent on the belt. The hallmarks in the fields depict scenes of martyrdom in detail. It may seem that the torment is depicted somehow abstractly, but for the people of Ancient Russia the image was read through the prism of folk tales, in which the heroic deed of Yegor the Brave was repeatedly praised highly.

Coat of arms, order and a mere penny

Starting from the 15th century, the iconography “The Miracle of George about the Serpent” is becoming more complicated, enriched with new details. The image of Christ appears in the heavenly segment or the image of His blessing right hand, a figurine of a soaring angel or two angels laying a crown on the head of George. Some icons depict equestrian troops leaving the city gates to meet George.

For many centuries, icon painters, sculptors and artists have depicted St. George. The coat of arms of Moscow from the time of Ivan III adorns his image. In the XVI century, St. George appeared on Russian coins. Even the name "penny" is associated with the image of the great martyr, because a warrior with a spear in Russia was called a spearman. The Order of St. George was the highest award for soldiers and non-commissioned officers in pre-revolutionary Russia. The image of a young warrior who sacrificed his life for Christ and is ready to fight the terrible serpent still inspires icon painters. A striking example is the image of St. George of the modern icon painter Dmitry Hartung, which combines the features of a canonical icon and echoes of antiquity.